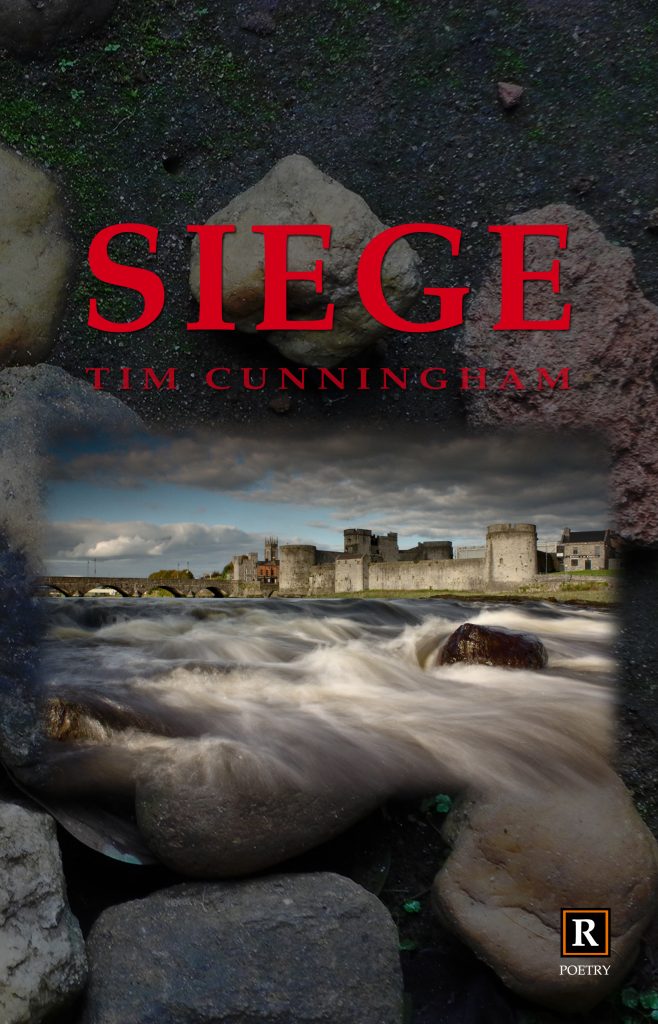

Knute Skinner: “A long-time admirer of Tim Cunningham’s work, I heartily recommend his latest collection, Siege.”

Every poem in Limerick born poet Tim Cunningham’s fourth collection, Siege, is of universal application, but the physical locus and emotional heart is (are) that ‘ancient city schooled in the hardships of war’. He casts a warm eye on Limerick, wheree caas

he was born in 1942, but the vision is twenty twenty.

The soul of the book is people’s lives, lives lived in a place and time of extraordinary change ranging from post-war poverty and emigration through the dominance of religion being eclipsed by an increasingly materialistic phase, culminating in the ‘Celtic Tiger’ years, to today’s sobering uncertainties.

The collection’s themes develop organically from the lives of those very real people, all as heroic in their own quiet way as the men who held the walls and the women who threw them bread. Their struggle with life’s ‘slings and arrows’, tempered by its constant joys, is Everyman’s. Here the tapestry’s intricate threads are woven in the drizzle on the Shannon, in O’Connell Street, King John’s Castle, St. Michael’s Church, Mathew Bridge, Garryowen, every kitchen and sleepless pillow.

Siege is a celebration of life and an intimate paean to where particular lives at a particular time were, and are being, lived; what used to be called a work of pietas.

Book Review – R.V. Bailey, Envoi

SIEGE, Cunningham’s fourth collection is a selection of the poems from the earlier three, with some new poems. It is really, I suppose, an extended love-letter to Limerick, to his parents and his past, to a world that is no longer accessible except through such tributes. This distillation of work has all the richness of a slow-cooked casserole, its carefully blended ingredients varied and individual, its nourishment undeniable. The early poems look back to his parents: his young father’s letter home from the battlefield, written in pencil and (as he’d directed) later inked in by his widowed mother:

I part the yellowing pages now

Brittle as fallen leaves;

Unbandage the past …

… The poem’s pencil-sketch of love,

Of life disappearing

Like wrens into a bush.

I read his testament,

Follow the vowel and consonantal

Roads we might have walked.

But mostly I watch her hand,

Observe it tracing faithfully

The loop and line of letters;

Her pen climbing his wordscape,

Its warm ink intimate on pencil

Like skin on skin.

This dignified, moving piece, in its quiet way, illustrates the quality of what’s to come in the collection, fact and feeling linked in the economy of words, creating small moments of huge significance. In other poems the soldier remembers home, and Sunday Mass, and

she keeps his letters in the empty box of chocolates they shared the night before he left. It’s a miracle to be able to write about such intensity of love, such sadness, without a syllable of sentimentality. But Cunningham is good on the matter-of-fact everyday quality of experience. He knows the power of simple words, and uses them deftly.

An Irish Catholic childhood: neighbours, school-fellows (‘Noel who could walk home on his hands’), the corrections the boys made after their essays were returned:

Later, we changed the jobs,

The cars, the houses, even wives;

Everything on which we felt

Perhaps we could improve…

Inevitably much of such material is elegiac: the playmate who collapsed and died, the hawk shot, the ‘snap and crunch of bones’ as old beliefs – ‘the credos and catechisms’ – ‘like martyrs are broken on a wheel’; as the ritual pageantry of liturgy, the church ‘our

theatre and concert-hall’ –

All this and the comfort of belief.

Youth gifted with the joy of possibilities…

fades, the stone steps that lead there now ‘slippery with rain and holy water’. ‘The Lepers’Squint’, the hole in the Cathedral’s wall where lepers could watch the Mass is now metamorphosed into the cash dispenser, the hole in the wall where ‘We congregate, press pin numbers,/Squinting in the sun.’ ‘Religion’s good news’, he tells us, ‘is lost in the post.’

Irish history, as well as personal memory, is here: this is no private love-letter, despite the title poem’s passionate declaration. And there are terrible tales to be told, of the woman who wheels the empty pram, the boy who fell into the tanner’s vat, the lives ‘sacrificed’ in the days before ‘the convent wall is broken’; the miscarried child lies like a fish in the basin.

But there is also a quiet wit, a harvest of gentle irony in these Limerick vignettes. Read Siege and you enter another world. Cunningham gives you a real place, and he peoples it with a cast of characters recognisable, everyday, insistently individual. The plot? Why, it’s often religious. It’s Irishness, past and present. The tone is compassionate. The perspective is honest, and the poems are as fresh and readable as tomorrow’s newspaper.

Book Review – Gabriel Fitzmaurice

Siege (Revival Press)

Tim Cunningham

“Siege” is a beautiful book, as Limerick as the Treaty Stone, as universal as the Church. Here poetry is prayer, indeed many of the poems are set in churches. But it isn’t a simplistic prayer; it is a prayer that has weathered frost and drought. It is a prayer that contains doubts in every sense of the word “contains”, where “Beliefs, like martyrs, [are] broken on a wheel”, where the “Virgin’s back is to the wall”, but he can talk of “resurrections” in the ticking of a mended watch. Here the hell fire sermons of his youth are tempered by memories of the old Latin Mass, of the “God Who gives joy to [our] youth”. In his very Catholic childhood, the one Protestant, Mrs Kirby, is different “As if she had measles/Or came from the North Pole”. But, in the end, she is the spirit of Christmas giving gifts on Christmas Day.

Tim Cunningham’s book is a homage to the city of Limerick, a city as different to Frank McCourt’s as chalk is to cheese. He revels in memories of the Corbally Plot, the old Savoy, the Treaty Stone, the Royal George Hotel, Saint John’s Castle, Tim Glynn’s window in Rutland Street, Garryowen market, O’Connell Street. It is a place of the imagination as much as it is actual, where “A stray piebald outside the school/Was Galloping Hogan’s. The Model/T’s backfire was Ballyneety’s/Munition Train exploding/Still across hurt centuries”. It is the city he loves. He writes:

“I love this city as if hair

Fell soft about its shoulders,

As if its eyes were lakes of naked joy

And its voice the music of spring”.

But still there is the Magdalene laundry, there is emigration, there is death. Tim Cunningham writes very tenderly and poignantly of last things – of dying and death and the life that must go on after death. He writes of the young mother’s husband who didn’t make it home after the war, he writes of his grandfather whose wisdom and love of life shone clear through the windows of a terminal ward, of his grandfather who, contrary to what the lawyers stated, did not die intestate such was his love of life.

Tim Cunningham reflects on history in this book – of 1798, of Patrick Sarsfield, Ginkel, the Treaty Stone, the Wild Geese. But he is not a prisoner of that history – if there was once “A narrow view of history”, we have progressed to a “wider view” to which he can return, “creation’s oils still wet -/Perched on the crow’s nest/Of [his] grandfather’s broad shoulders”.

“Siege” is a quiet book where sparks guide memory. It is beautifully written. And it is beautifully produced by Revival Press. It is a pleasure to congratulate them both.