Richard W. Halperin: “Vermeer language. An accessible voice, full of the colours of his native Limerick. The small and the large are the same size, because nothing is small. In this book Tim Cunningham, one of Ireland’s finest poets, steps out of his previous collections as if they were discarded shells, and brings us to new perceptions. Of how poetry can reveal, acknowledge, heal. Everything has its homely touch, as when the poet as a small child hears a reminiscence of the father he does not remember, killed in Italy in the War:

‘So, like hot tea from a saucer

I sipped away at absence, slurped clues

From photos standing to attention

On the wall or on the dresser at their ease . . .’

A grand book in view of its scope and its risk-taking: the banal and the hilarious, TV watching and worse; Catholic liturgy at its most damaging and at its most consoling; Limerick under the fists of the British, then under the fists of Irish politicians and bankers; unexpected associations, as in a poem ‘Lifebuoy’ which touches upon Bernini, wagtails, ice-cream, rescue, drowning. Throughout the book, the Shannon – ‘Lady River’ – running as an indifferent and a healing force. Anything, even something rotten, is privileged to come into this man’s field of attention. Almost memories, because there seems to be recall not just from after the experience but also from before, as in Wordsworth. So, a ‘Daffodils’ effect. Poems to reread. A wonderful book.”

New Writing from Ireland – SOUTH WORD Journal

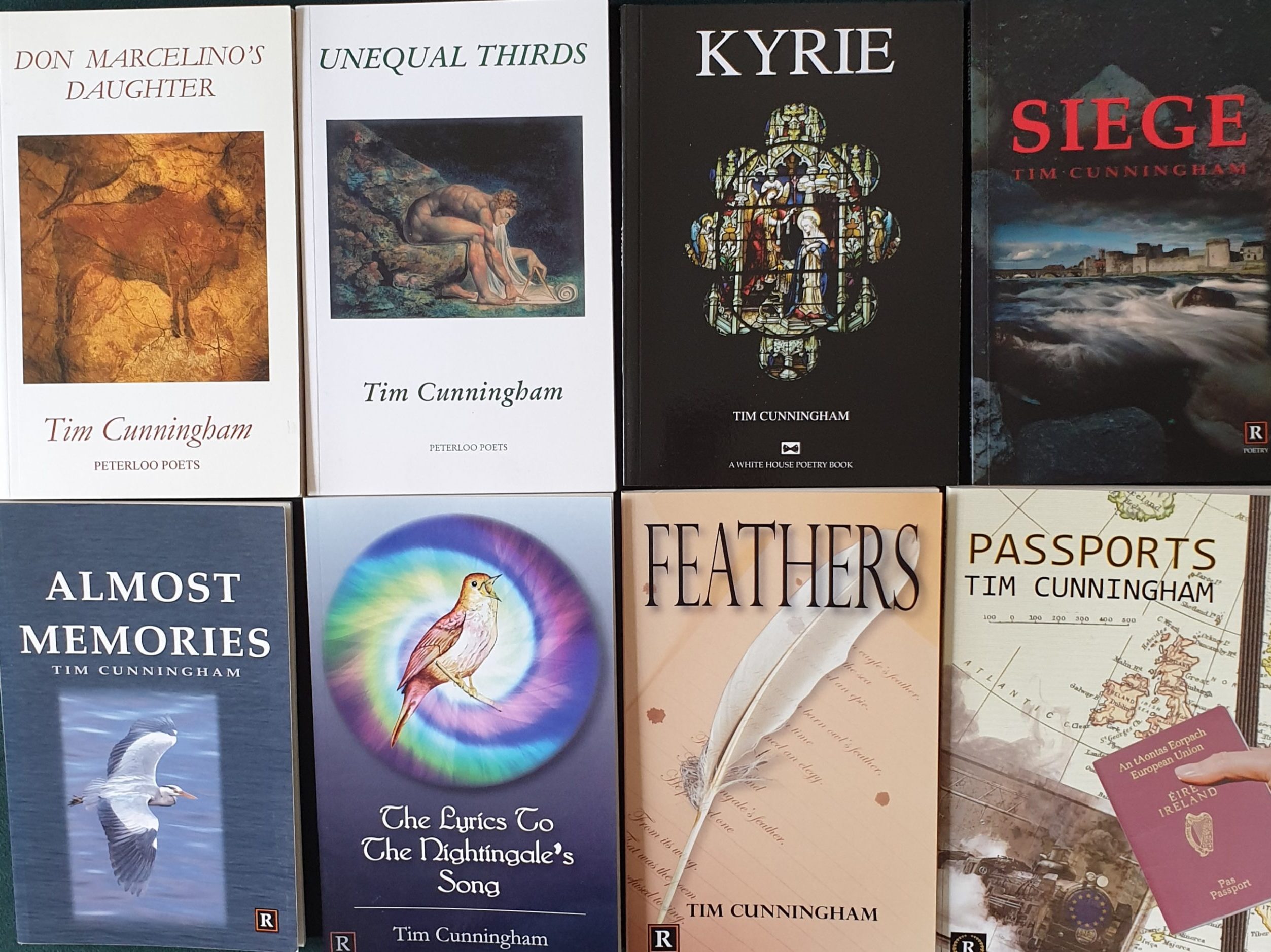

Almost Memories by Tim Cunningham is unmistakably informed by the poet’s desire to examine what might tentatively be identified as ‘Irish’ preoccupations and themes, including, according to Richard W. Halperin’s blurb, “Catholic liturgy at its most damaging and at its most consoling; Limerick under the fists of the British, then the fists of Irish politicians and bankers.” It sounds like heavy going, so it was a pleasant surprise to find that Cunningham’s best poems are often those about the Irish countryside. Although it’s at first glance nothing we haven’t seen before in the context of Irish writing, the poet manages to peel back the layers of countryside living to reveal it to us in new and intriguing ways.

‘Seven Wonders of the Parish’ is a fine example of Cunningham’s control of language, and of how he uses it to make us feel that we are reading about conventional topics for the first time. The poem consists of seven stanzas of three lines each, and each stanza is given over to one countryside image, so that our impressions of the place are fleeting but memorable. Thus a vixen and her cubs ‘ignite the broken wall’ and the traces of a sparrow in snow are written in ‘fluent Japanese.’ The poem’s subtle beauty lies in not ascribing any meaning to the landscape, but are mere descriptions of a scene—similar to the haiku tradition, hence the Japanese reference—and all that is necessary to give the poem resonance is the language Cunningham chooses to paint the scene in our minds.

A grandmother’s cottage appears again and again in these poems, clearly a place of deep personal significance to the poet, and with it the collection’s title is assuredly earned. These poems invoke a world informed by “almost memories” —half-formed things echoed by a cottage’s sealed half-door, like “some pharaoh’s tomb” where a woman watches her young grandson play as she watched her now-dead son play many years before. ‘In My Father’s House’ contains the striking detail of its narrator visualising “a path of fairy tale stepping stones” to his grandmother’s cottage, and the poem is like part of that path itself, leading the reader back to a disappeared world that is vivid in its re-imagining. Of course, the vanishing of a simple, rural way of life such as that which is described here is a well-trodden theme in Irish writing, but it’s a testament to Cunningham’s skill and his unmistakably tender treatment of the subject that allows us a glimpse of that time with a fresh perspective.

Night too was the haunt of Jack O’Lantern Leading astray those already shawled Unless they turned their jackets inside out But who wore coats in summer?

An absent father is a topic that repeatedly appears in this collection, as are the almost-memories that take root in the gap between what a child remembers and what he thinks he remembers. The collection takes its title from the opening poem, in which the narrator sifts through not-quite memories of his father “like searching for the ball / in the tall grass and thistles.” Meanwhile, ‘Ghost Ship’ displays an astonishing grasp of language and of the extended metaphor of a father symbolised by a ship in a bottle, which gives rise to other metaphors that are deftly woven into the overarching narrative: “My mother kept his memory bottled up / As if it were a vintage for herself / Alone.” Later, the wedding rings that belonged to the narrators’ parents are described as “[s]ymbols of a lasting love cut short / By the ring on a World War Two grenade’”

Cunningham is at his best with solid imagery and restrained emotion, as when in ‘Taking Down the Decorations’ an older woman putting away Christmas decorations is reminded of how a now-absent male figure “brought / each bauble home, each paper bell” and the packed-away decorations are movingly described as “the glittering strata of a life.” But he has a tendency to stray into overly-obvious sentiment. ‘Losing His Grip’ in which the subject imagines a dying person trying to hold onto his hand as she dangles from a cliff, is let down by its clichéd ending:

Nothing hurts more Than this holding on, Nothing, except the letting go.

I was much more attracted to the poems with a personal aspect than to those with more political overtones, such as ‘A Candle in the Window’ – which has Ireland’s history of famine and emigration at its core – or ‘Proclamations, 1916’, which pretty much does what it says on the tin without bringing any real new perspective to the days leading up to the Easter Rising. But this is a subjective opinion within the infamously subjective sphere of poetry, and Cunningham, who has already published four collections previous to this one, has produced an undeniably accomplished book in which virtually any lover of poetry will find something that appeals. And I predict that not many could fail to be moved by ‘Jigsaw Man’, which examines the life of a man and the pieces that are missing, such as an absent son and daughter. Cunningham gently reminds us that no life is ever entirely complete, and that it is ostensibly insignificant pieces that can turn out to be the most important: “the fireside / songs and stories, those riverside walks.” With its tributes to loss, to the countryside and to love, Almost Memories is itself a quietly triumphant celebration of such pieces of a life.

©2015 Róisín Kelly